Towards the end of Andrzej Wajda's 1956 film Kanal, two exhausted survivors of the Warsaw Rising are fleeing through the city sewers. Struggling through the dark, stinking labyrinth, they suddenly notice a glow of diffused light coming from behind a bend in the tunnel: they have reached an outflow into the Vistula, and safety. As they come round the bend, the camera pans ahead of them to show an immovable iron grid cemented across the mouth of the tunnel.

Mona Hatoum's installation The Light at the End provokes something of the same feeling of helpless, inevitable horror. Hatoum is perhaps best known as a video and performance artist, but some of her strongest work has revolved around installation and environmental sculpture, notably Hidden From Prying Eyes (Air Gallery, 1987); this fits in well with the Showroom's excellent record in that area, including, during the last year, fine examples by Andrea Fisher and Ron Haselden.

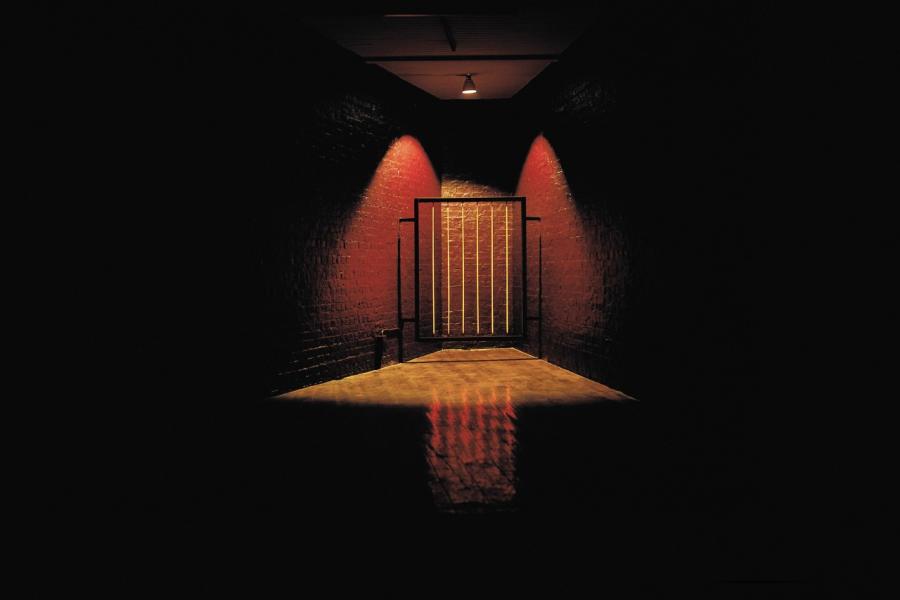

Hatoum's installation is in the triangular space at the rear of the gallery; the darkened room, painted flat black, is empty except for a simple rectangular grid embedded into the walls at the apex, some three feet away from the far corner. The five vertical bars of the grille are a bright, glowing orange; a single dim fixture in the ceiling above throws two sinister wings of light either side of the grid. As you stumble tentatively towards the corner, you realise it is becoming oppressively hot, and that the heat increases as you come nearer. There is nothing to stop you walking right up to the grid and touching it - but you would be well advised not to try, for the bars are not painted, but red-hot lengths of heating element. Grasp one, and it will burn your hand through to the bone.

The fact that the danger of physical hurt is so explicitely real at first takes Hatoum's work clear away from the realm of artistic allegory; yet the danger is only proposed, remains merely an unlikely possibility, unless of course you, the viewer, take that last step and touch a bar. And that temptation adds another dimension to the oppressive implications of the installation; like the simultaneous repulsion and attraction exercised by the void when one stands on the edge of a cliff or high building, the incandescent elements call out for experimentation, for verification. Can the wall behind them be touched, perhaps? At the very least, few viewers will resist carefully, fearfully moving a hand between the bars.

Hatoum has always been adept at articulating political concerns literally in terms of direct physical experience, a strategy which short-circuits rhetoric by suggesting that what is done to the body can be both a metaphor and a reflection of oppression. After a while spent in this malevolent environment, a number of associations are triggered; above all, memories of that sadly deluded Pentagon spokesman who, during the height of the Tet offensive, spoke cheerfully of seeing “light at the end of the [Vietnamese] tunnel”, but also of that unpleasant contemporary version of the martyrdom of St Lawrence, much in vogue among certain Latin American regimes, which consists of strapping a victim to a metal bedframe and running a live current through it. Beyond such references, however, what remains in memory is the grim simplicity of it all: a dark tunnel, and a dead-end sealed off by an implacable, glowing archangel.

© John Stathatos 1989

First published in Art Monthly, London, September 1989

Review of exhibition at the Showroom Gallery, London